Genre: Drama | Family | Psychological | Coming-of-Age

Ordinary People (1980) is a quiet, devastating masterpiece about grief, guilt, and the delicate fractures that lie beneath a seemingly perfect suburban family. Marking Robert Redford’s directorial debut, this intimate drama swept the Oscars—winning Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Supporting Actor—and remains one of the most understated yet powerful explorations of loss and emotional repression ever put to film.

Based on Judith Guest’s 1976 novel, the story unfolds in the affluent suburbs of Lake Forest, Illinois, focusing on the Jarrett family, whose flawless outward appearance masks a deep, festering pain. The family’s oldest son, Buck, died in a boating accident—a tragedy that shattered the family’s sense of normalcy and left wounds no one quite knows how to heal.

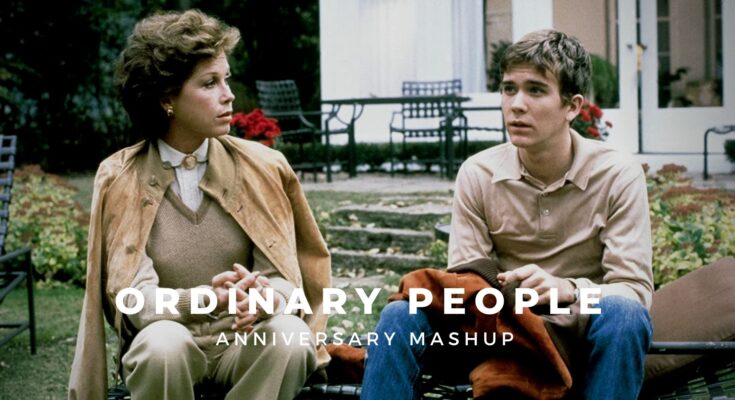

At the center of the story is Conrad Jarrett (Timothy Hutton, in a remarkable, Oscar-winning performance). After surviving the accident that killed Buck and a subsequent suicide attempt, Conrad struggles to navigate the suffocating expectations of returning to “normal life.” He drifts through school and swim practice like a ghost, weighed down by survivor’s guilt and feelings of alienation from his parents.

His father, Calvin (Donald Sutherland), is gentle and well-meaning but helpless in his attempts to hold the family together. His mother, Beth (Mary Tyler Moore, in a career-defining dramatic turn), clings to composure and appearances, unable—or unwilling—to show the vulnerability her grieving son needs most. Beth’s coldness is not villainy but a devastating armor against pain she refuses to name, and Moore plays her with heartbreaking restraint.

Desperate for a way out of his numbness, Conrad begins therapy with Dr. Berger (Judd Hirsch, who earned an Oscar nomination for his role). Their sessions form the film’s raw emotional core—tense, painful, but honest. Through these conversations, Conrad slowly confronts the guilt and anger festering inside him, even as the fragile bonds of his family begin to unravel under the weight of unspoken grief.

Redford directs Ordinary People with an understated, sensitive hand. There are no melodramatic crescendos or showy flourishes; instead, the film’s power lies in its quiet honesty and sharp observation of human behavior. Every glance, every awkward silence, every clipped line of dialogue feels painfully real—mirroring the distance we often maintain from those we love most when the truth is too heavy to hold.

The suburban setting is captured in soft, autumnal tones—comfortable houses, manicured lawns, cozy dining rooms that feel haunted by the absence of what once was. Pachelbel’s Canon drifts through the score like an echo of the peace this family can’t seem to find again.

When Ordinary People was released, it struck a nerve because it dared to show that real tragedy can exist behind well-kept fences and polite smiles. It wasn’t about big dramatic gestures—it was about the loneliness that can grow in families that don’t know how to speak their pain aloud.

More than forty years later, the film still feels timeless in its quiet reminder that surviving tragedy is rarely about heroics—it’s about finding the courage to be honest with ourselves and each other, no matter how messy or shameful that honesty might be.

Tender, heartbreaking, and deeply human, Ordinary People remains a profound portrait of a family in the aftermath of unspeakable loss—and a testament to how connection, however imperfect, is the only way through the darkness.