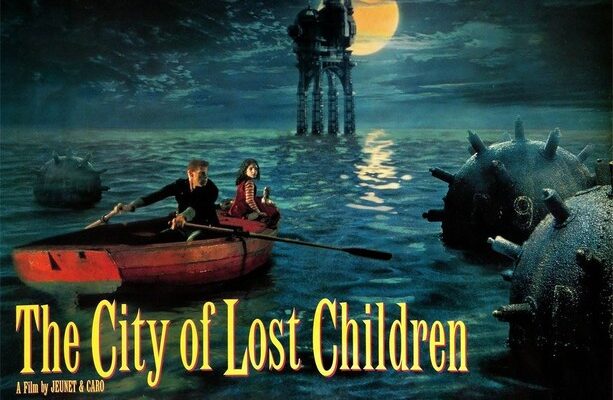

Genre: Fantasy | Science Fiction | Dark Fairy Tale | Surreal Adventure

The City of Lost Children (La Cité des enfants perdus) is a richly imagined fever dream—a fantastical, sinister fairy tale that looks like it crawled out of a dusty storybook and took up residence in your subconscious. Directed by the visionary French duo Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet (who also co-directed Delicatessen), this 1995 cult classic is a breathtaking dive into a world where the strange and beautiful collide in ways both enchanting and unsettling.

Set in an unnamed, timeless, and fog-choked port city, the story revolves around a nightmarish villain named Krank (Daniel Emilfork), a mad scientist who cannot dream and is aging prematurely as a result. Desperate to steal what he cannot produce, Krank kidnaps children and siphons their dreams in a vast, mechanical lair perched above the sea—a decaying oil rig brimming with eerie contraptions, cloned henchmen, and whispering secrets.

When Krank’s minions abduct Denree, a small boy with a wide-eyed innocence, his adoptive brother One (played with gruff tenderness by Ron Perlman) sets out on a quest to rescue him. One, a gentle strongman from the circus, finds an unlikely ally in Miette (Judith Vittet), a fiercely clever orphan girl who leads a gang of streetwise children navigating the city’s Dickensian underbelly.

Together, they plunge into a labyrinthine world of mechanical fleas, twisted cults, underwater divers, and sinister Siamese twins who run a gang of child thieves. The story, if you can call it that, is less a straight path and more a series of dreamlike detours—visual set pieces that feel like pages from an illustrated nightmare.

What makes The City of Lost Children unforgettable is its style. Jeunet and Caro craft a world bursting with Rube Goldberg machinery, steampunk gears, damp alleys, and foggy docks, all rendered in lush green and sepia tones that give every frame the texture of an antique photograph come to life. The production design, practical effects, and elaborate sets feel tactile and surreal, like Metropolis crossed with a children’s nightmare.

The film’s atmosphere is as crucial as its plot—a blend of fairy tale wonder and grim, carnival grotesquerie. The performances, especially Perlman’s tender brute and Vittet’s wise-beyond-her-years Miette, anchor the film’s wild flights of fancy with genuine heart. Beneath the mechanical marvels and twisted villains lies a simple, powerful theme: the longing for dreams, family, and lost innocence.

Like its spiritual siblings Brazil and Pan’s Labyrinth, The City of Lost Children is cinema that embraces the weird and wondrous without apology. It’s not just a story—it’s an experience, a place you visit in your mind and wonder if it ever really let you leave.

Almost three decades later, it remains a gem of 90s European fantasy cinema—a testament to what happens when filmmakers dream with their eyes wide open and build worlds where even lost children can find their way home, if only in their dreams.